open office spaces aren’t new, and never really worked

it’s not surprising that a dysfunctional office culture is bad news for everyone involved. stressed-out employees take more sick leave, make more mistakes, and produce less than healthy, well-adjusted ones. this is true from the mailroom all the way up to the executive suite.

what is surprising is the number of offices that unknowingly promote dysfunctional work cultures within their walls—or lack thereof. almost 70 percent of all offices have implemented an open floor plan, and the results show what years of studies have already concluded: open offices don’t work.

although Silicon Valley has been trumpeting the value of the open office for years, the success of open office culture’s biggest advocates – Facebook, Google, Autodesk, Samsung, and the like—can’t be chalked up to this outdated and over appreciated office design.

the truth is that the open office isn’t new, and it never really worked the way many people intuitively felt it would. in fact, open offices have been shown to make employees withdraw from one another, interact less meaningfully (but more frequently), and get distracted more easily.

i’m not saying that offices should go back to the cubicle, but if we are going to find an ideal office space for today’s workers, we’ll have to start with the reasons why that symbol of corporate hierarchy was invented in the first place.

the year 1964: introducing the cubicle

a great number of important things happened in 1964: Martin Luther King Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Lyndon B. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater in the presidential race, which escalated the Vietnam War amid deepening civil unrest. The Beatles released their first album to American audiences. but amid all of this, another world-changing event was quietly taking place: a home furnishings designer named Robert Propst invented the cubicle.

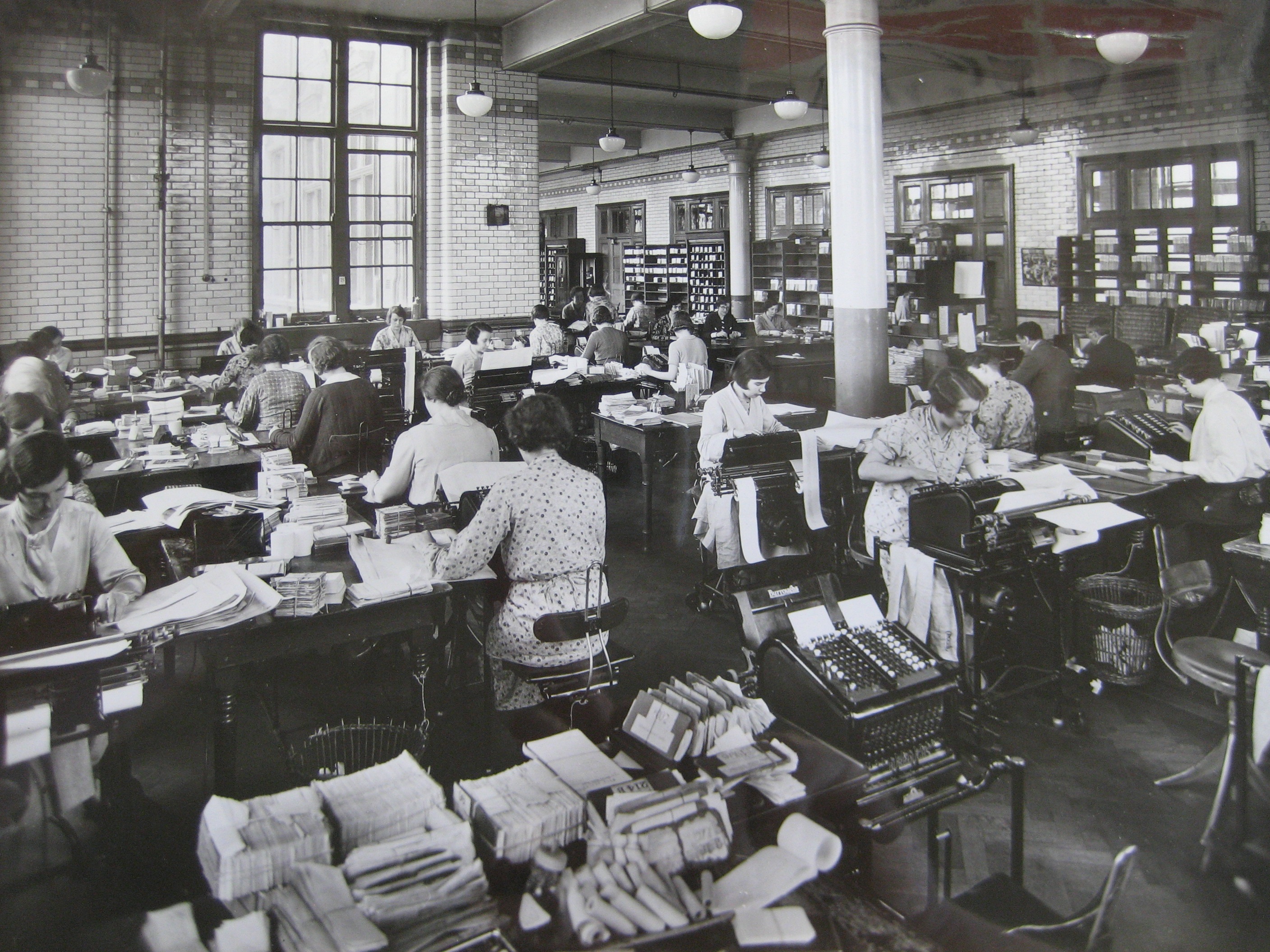

Until Propst came along, the office environment had remained largely unchanged since the industrial revolution. the overwhelming majority of office workspaces featured what today’s hippest Silicon Valley executives would call collaborative open floor plans. here’s an example:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/89/Blythe_House_preparing_totals_for_daily_balance_1930s.JPG

in the parlance of the day, this was called a bullpen. it’s still the go-to office architecture for some institutions and industries, notably law enforcement (watch almost any police or detective show released in the past few decades, you’ll see it), newspapers, and finance.

Propst invented the “Action Office” system to address the privacy-deficient workplace panic that he had grown up with working in the bullpen. in the true spirit of inventions ahead of their time, it immediately flopped; Propst’s firm, Herman Miller, sold only a handful of systems. but things started to change.

in the late 1960s, new tax laws made it easier for companies to write off the costs of depreciating assets, like office furniture. in the 1970s, the energy crisis led to regulations that required offices to be more energy efficient. in the 1980s, corporate mergers and acquisitions became commonplace, leading to higher employee turnover—an ideal situation for the modular cubicle-based floor plan. by the 1990s, the internet enabled computer-dominated offices around the globe. the stage was set.

but the office culture of the 1980s and ’90s was a strikingly different place than the one that Propst had originally envisioned. in an urge to maximize production and efficiency, America’s middle managers began using the cubicle to stuff as many workers into as tight an area as possible—the “cube farm.” Propst himself saw this and despaired over the corruption of his original vision, calling the office culture that cubicles helped form a kind of “monolithic insanity.”

the open office makes a comeback

with the dizzying array of technological advances that took place between the 1980s and the 2000s, a change in the way office culture works was virtually guaranteed. the digital tools widely available today, often for free, allow a single employee to do the work it would have taken an entire department to accomplish in the 1960s.

at the same time, a heightened sense of individualism arose in almost every level of American society. newly empowered employees felt resentful of the authority-driven company culture they grew up in. the response was as physical as it was metaphorical—they broke down the walls between employees.

the problem is that the walls between employees were never the problem in the first place. a 2013 Harvard Business Review study found that factory employees were more productive when working in private. the top performers used privacy to test productivity-boosting ideas before communicating them to management. privacy ensured a distraction-free environment, while openness simply led employees to look busy.

how to synthesize the best of both worlds

in an ideal office workspace, employees feel empowered to experiment with ways to improve productivity in an environment safe from micromanagement. in many cases management should put less emphasis on the process itself and more emphasis on the outcome that comes from the process.

promoting flexibility and collaboration within the organization is great. but the nature of work in the twenty-first century puts pressure on the employee to establish a flexible, collaborative environment with the employer, not necessarily with other employees. this is why 90 percent of employees working in open office spaces report higher levels of stress, conflict, and turnover.

instead of throwing all of their employees into a bullpen-style open office, executives can get more production out of employees through a handful of adjustments to the workplace. for one, reintroducing a level of privacy, even if it’s done in the form of remote work for a set number of days per week. this kind of adjustment can be reinvigorating for a previously unmotivated employee. in my opinion, it’s not a problem that furniture can solve.