how to take control of your life by forming positive habits: part one

when was the last time you consciously made an effort to do something courageous, wise, or just? it’s probably been a while, because the fast-paced world we live in doesn’t leave a lot of room for intentionally cultivating the virtues of courage, wisdom, or justice.

but these virtues are exactly what we need most. when you look at people who are both professionally successful and happy with their personal lives, you will invariably see habits that reflect these behaviors.

similarly, when you look at people who are unsuccessful in their professional and personal lives, you will almost certainly see them perpetuating that state through bad habits. the most damaging ones are often the easiest to rationalize, especially when the culture we live in actually encourages us to do so.

we constantly hear about the habits of the world’s most successful business leaders have, like Bill Gates, who reads 50 books a year, or the workout regimen of Bob Iger. but we rarely hear about how they developed those habits in the first place.

this article, the first in a two-part series, directly addresses that issue. the second part will show how long it takes to truly establish good habits, so that they become second-nature—and help you unlock your potential and change your life for the better.

habits are how you manage a brain on autopilot

according to a study published by Cornell University, the average american makes around 35,000 decisions every day. we are not fully conscious of most of these decisions; they take place just under the veil of our conscious mind.

the human brain has evolved to interpret experience and steer the body toward an appropriate response. the vast majority of these responses don’t require conscious thought, and even the ones that do, if repeated often enough, no longer will. taking the time and effort to build good habits and overwrite bad ones actually revises the brain’s autopilot program.

some highly successful and industrious leaders—like Mark Zuckerberg and Barack Obama—subscribe to the theory of decision fatigue, which claims that the human ability to make conscious choices wears out over the course of the average day. that’s why both Zuckerberg and Obama intentionally limit their wardrobes. it’s one less unimportant choice to make.

these strategies help the brain conserve energy and steer behavior toward successful outcomes. they become habits that lead to greater professional and personal success.

habit building is about structures of support, not willpower

almost everyone has an intuitive idea about how habits form. in most cases, the opinions of parents, mentors, and close friends form a substrate upon which habits grow. they often stretch back into early childhood and form an entire system of behavior that defines a person’s activities in day-to-day life.

human beings tend to participate in the systems of behavior established by their closest confidants, regardless of whether those systems are consistent, coherent, or morally valid. this is because they come with a cultural structure of support. both Plato and Aristotle called these structures conventions, and most people simply accept them as the norm without thinking about them. the habits they build as a result reflect those conventions’ shortcomings. but we can change these habits if we work (and think) hard enough about them.

everyone feels good about establishing a good habit—at first. you start meditating in the mornings, or go to the gym a few times, or express your gratitude and appreciation for a friend. but eventually something comes up and gets in the way, or you simply forget. enthusiasm is the easy part. commitment is the hard part.

anyone who tries to build a new habit without laying down the foundation of successful habit building is putting all of the responsibility for success on a single element of the conscious human mind: willpower.

the problem is that willpower isn’t enough. clinical psychologists have found that, in most cases, willpower is not sufficient for enacting positive change over a long period of time. Aristotle referred to this as akrasia, which roughly translates to “incontinence” or “lack of mastery.”

counselors and criminal psychologists who work with drug offenders use the term white-knuckling to define the willpower-based approach. study after study concludes that incarcerated drug addicts who rely on willpower for rehabilitation stand a significantly lower chance of freeing themselves from addiction than those who are taken out of prison and put into rehab centers.

In this research, the change-making difference was participating in a positive environment that offered a structure of support. an environment that rewarded good behavior turned out to be far more effective than one that punishes bad behavior. willpower is still an important part of the equation, but it isn’t the whole answer.

how to commit to positive habit-forming behaviors

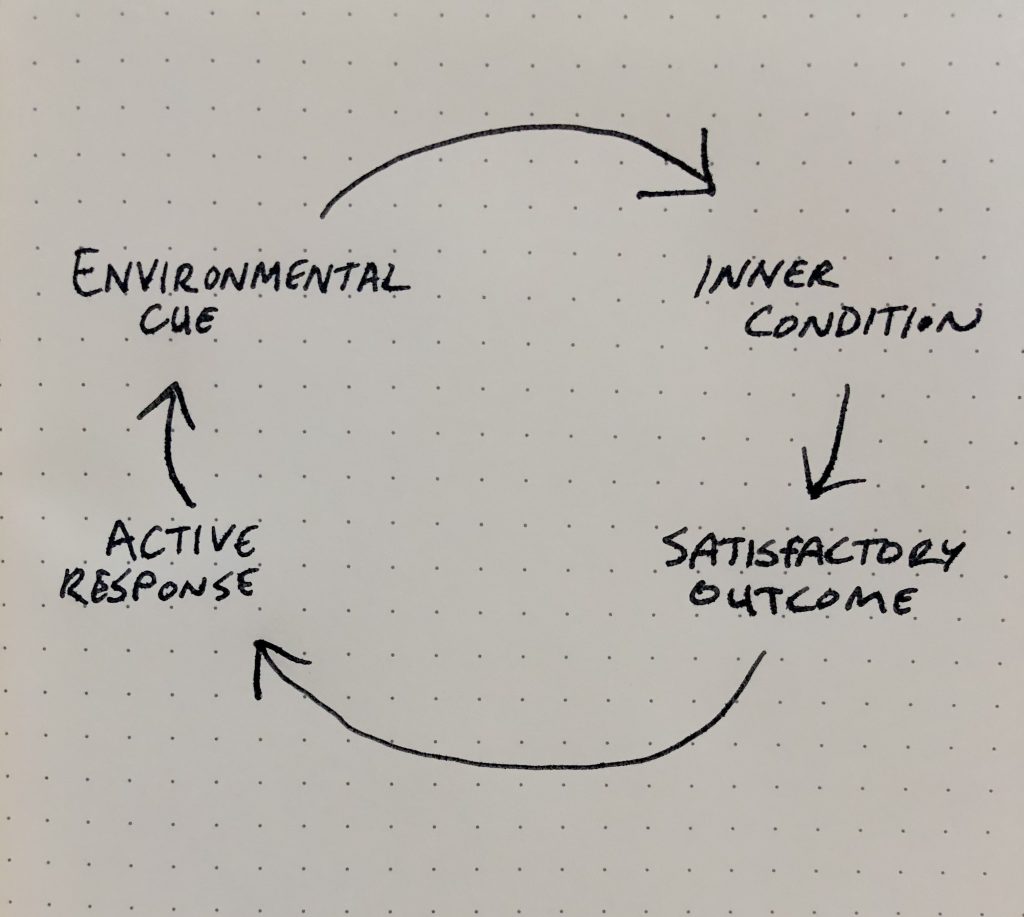

all habits draw their origin from a four-step feedback loop:

- an environmental cue. you hit an obstacle at work, for example.

- an inner condition. you feel frustrated because you’re stuck on a problem.

- an active response. you pull out your cell phone and scroll through your social media feed, or you take a break and smoke a cigarette, or you calmly consider the problem an opportunity to practice patience and improve your work ethic, so you get right to it.

- a satisfactory outcome. you either satisfy your frustration by turning away from the problem or toward it. whatever choice you make becomes associated with a feeling of relief.

see the illustration below of a habit loop inspired by James Clear:

the important thing to realize about these four steps is that only one of them is always within your control. your ability to control the environment is limited, and you can’t control the appearance of feelings like frustration, anger, fear, or joy, but you can control how you perceive those conditions. this will inform your response.

“The things you think about determine the quality of your mind,” wrote Marcus Aurelius almost two thousand years ago. “Your soul takes on the color of your thoughts.”

if you could rationally work out the response to every single one of the thousands of decisions you make every day, you could form excellent habits.. unfortunately, that’s not usually the case—ask anyone who ever tried to quit smoking.

in a world where much of what we do is already formed through habit, improving our habits allows us to improve the quality of our life. in part two of this series, i’m going to cover how that works, and how long it takes.